- Home

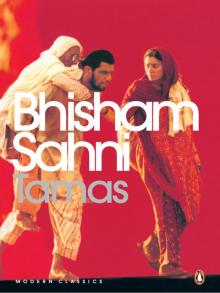

- Bhisham Sahni

Tamas

Tamas Read online

BHISHAM SAHNI

Tamas

Translated from the Hindi by the author

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

About the Author

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Copyright Page

TAMAS

Bhisham Sahni (1915–2003) was born into a devout Arya Samajist family in Rawalpindi (now in Pakistan). He went to school there, then went to Government College, Lahore, from where he took a Master’s degree in English Literature. He returned to Rawalpindi to join his father’s import business but finding the job too taxing, decided to teach at a local college. At the same time he also became involved in the activities of the Indian National Congress.

After Partition in 1947—his family settled in India and Bhisham Sahni took the last train to India—he settled down in Delhi and began to teach at a Delhi University college. His first collection of short stories, Bhagya Rekha (Line of Fate) was published in 1953. In 1957, Bhisham Sahni moved to Moscow to work as a translator at the Foreign Languages Publishing House. He worked in the USSR for nearly seven years during which time he translated several Russian books into Hindi. He returned to India in 1963 and resumed teaching in Delhi. He edited a literary journal, Nai Kahaniyan from 1965–67 and began working on Tamas, a novel based on his experiences as a young man, in 1971.

Bhisham Sahni won the Sahitya Akademi Award for Tamas in 1976. He also won the Distinguished Writer Award of the Punjab Government, the Lotus Award of the Afro Asian Writers’ Association and the Sovietland Nehru Award. He published seven novels, nine collections of short stories, six plays and a biography of his late brother, the actor and writer Balraj Sahni. Many of his books have been translated into various foreign and Indian languages. In 1998 he was conferred the Padma Bhushan by the President of India.

To Balraj, my brother

1

The clay lamp in the alcove flickered. Close to it, where the wall joined the ceiling, two bricks had been removed from the wall, leaving behind a gaping hole. With every gust of wind, the flame in the clay lamp quivered violently and long shadows flitted across the walls. But as soon as the flame steadied again, a thin line of smoke would rise from it in a straight line, licking, as it went, the side of the alcove.

Nathu was already breathless. He thought, perhaps it was his heavy breathing which caused the flame to quiver so violently. He slumped on the floor, his back resting against the wall. His eyes again fell on the pig. The pig grunted and put its snout to some sticky peel or rind in the garbage which littered the entire floor. With its pinkish snout, it had already licked Nathu thrice on his shins, causing him searing pain. At times the pig would begin walking along a wall, its eyes on the floor as though looking for something. It would then suddenly squeal and start running, its little tail curling and uncurling. Rheum, oozing from its left eye had trickled down its snout. Its bulging belly swayed from side to side as it walked or ran. By constantly trampling over the garbage, the pig had scattered it all over the floor and now a foul stench from the garbage, the pig’s heavy breathing and from the pungent smoke of the linseed oil burning in the clay lamp pervaded the room making it unbearably stuffy.

Though drops of blood lay spattered on the floor, the pig did not seem to have received a scratch on its body. It was as if for the last two hours Nathu had been plunging his knife into water or a heap of sand. He had struck the pig several times on its belly and shoulders, but on pulling out the knife, only a few drops of blood would ooze out and trickle down to the floor. There was no trace of any wound or stab. A thin, red line of a scratch or a tiny blot were the only visible signs of his efforts. Every now and then, with an angry grunt, the pig would either rush towards Nathu’s legs or begin running along a wall. Nathu’s blade had not gone beyond the thick layers of fat to reach the pig’s intestines.

Why of all the creatures, Nathu thought, had this despicable brute with its fat, bulging body, a snout covered with thick white hair like that of a rabbit’s, thorny bristles on its back, fallen to his lot to tackle?

Nathu had once heard someone say that in order to kill a pig, one should, first of all, pour boiling water on it. But where was he to get boiling water from? On another occasion, one of his fellow-chamars, while cleaning a hide, had casually remarked, ‘The best way to kill a pig is to catch it by its hind legs, twist them hard and turn the pig over on its back. While it is struggling to rise, one should cut open its jugular vein. That will finish off the pig.’ Nathu had tried all the devices but not one had worked. Instead, his shins and ankles were badly bruised. It is one thing to clean a hide, it is quite another to slaughter a pig. He cursed the evil moment he had agreed to do the job. Even now, had he not accepted the money in advance, he would have pushed the damned creature out of the hut and gone home.

‘The veterinary surgeon needs a pig for his experiments,’ Murad Ali had said, as Nathu stood washing his hands and feet at the municipal water tap after cleaning a hide.

‘A pig?’ Nathu had exclaimed, surprised. ‘What am I to do with it?’

‘Get one and slaughter it,’ Murad Ali had said, ‘There are many pigs roaming around the nearby piggery, push one into your hut and kill it.’

Nathu had looked askance at Murad Ali’s face.

‘But I have never killed a pig, Master. If it were flaying an animal, or cleaning a hide, I would have been glad to do it for you. But killing a pig, I am sorry, I have never done it. It is only the people in the piggery who know how to do it.’

‘Why should I come to you then knowing that the piggery people can do it? You and you alone shall do this job.’ And Murad Ali had shoved a rustling five-rupee note into his pocket.

‘It is not much of a job for you. I couldn’t say no to the vet sahib, could I?’ said Murad Ali, then added rather casually, ‘There are any number of pigs roaming about on the other side of the cremation ground. Just catch one of them. The vet sahib will himself do the explaining to the piggery people.’

And before Nathu could so much as open his mouth, Murad Ali had turned round to leave. Then, stroking his legs softly with his thin cane stick, he had added:

‘The job must be done this very night. At dawn the jamadar will come with his pushcart and take the carcass away. Don’t forget. I shall tell the fellow myself to take it to the vet sahib’s residence. Understand?’

Nathu had stood with folded hands. The rustling five-rupee note that had gone into his pocket had made it impossible for him to open his mouth.

‘People living in this area are mostly Muslims. If anyone sees it, there can be trouble. So be careful. I too don’t like getting such jobs done. But what to do? I couldn’t say no to the vet sahib.’ And flapping the cane against his legs, Murad Ali had left.

Nathu could not refuse either. How could he? He dealt with Murad Ali almost every day. Whenever a horse or a cow or a buffalo died anywhere in the town, Murad Ali would get it for him to skin. It meant giving an eight-anna piece or a rupee to Murad Ali but Nathu would get the hide. Besides, Murad Ali was a man of contacts. There was hardly a person, connected with the Municipal Committee, with whom he did not have dealings.

Waving his thin cane stick and walking jauntily along the road, Murad Ali was a common sight in the town. He wo

uld suddenly appear in one or another of the lanes or by-lanes. Everything about him, his swarthy face, his bristling, black moustaches, his small, ferrety eyes, the knee-length khaki coat he wore over a white salwar, even the turban on his head, all combined to make him look distinctive. Without any of these, even without his thin cane stick, or the well-bound turban, he would not be what he was.

Murad Ali had left after issuing his instructions, leaving Nathu in a tight spot. How was he to catch hold of a pig? At one time he had even thought of going straight to the piggery which stood on the outskirts of the town and telling the folks there to get a pig slaughtered and have it sent to the veterinary surgeon. But he could not so much as lift his foot in the direction of the piggery.

It had not been easy to draw the pig into the hut. The pigs were there, roaming about and sniffing at the rubbish that lay around. But it was a different matter altogether to lure one into the hut. All that Nathu could think of was to carry armfuls of wet hay and put it in piles outside his dilapidated hut.

Three straying pigs, wandering along dung-heaps and pools of stagnant water, chanced to come towards his hut. One of them sauntered into the courtyard and began sniffing at the pile. Nathu promptly shut the gate behind him. He then ran across the courtyard, opened the door of the hut, and picking up his lathi, drove the pig inside. Fearing that someone from the piggery might come that way and become suspicious on hearing the grunts of the pig, Nathu carried an armful of wilted hay into the hut and made small piles of it on the floor. The pig was soon absorbed in picking at the piles and Nathu, greatly relieved, came out and sat in the courtyard to have a quiet smoke. He smoked one bidi after another and waited for night to fall. When, at last, he went inside it was already dark. But what he saw in the unsteady light of the clay lamp, made his heart sink. The entire floor was littered with rubbish and a foul smell filled the room. As his eyes fell on the ugly, bloated pig, Nathu cursed himself for having taken on so repulsive and hazardous a task. He was half-inclined to throw open the door and drive the despicable creature out.

And now it was past midnight. The pig was still strutting about leisurely in the midst of the rubbish littered on the floor. All that Nathu had achieved was a few drops of blood on the floor, a couple of scratches on the pig’s belly, and a few nasty bruises on his own shins where he had been butted by the pig’s snout. Panting for breath and sweating profusely, Nathu could see no way out of the mess into which he had landed.

Far away, the tower-clock in the Sheikh’s garden struck two. Nathu stood up, nervous and perplexed. His eyes fell on the pig standing in the middle of the room. It urinated, and as though irritated by what it had done, began running along the right-hand wall of the hut. The wick in the clay lamp spluttered and long shadows swayed eerily across the walls. Nathu’s situation had not changed a whit. The pig, its head bent, would now and then stop to sniff at some bit of rubbish, then resume walking along a wall, or grunt and start running, its thin little tail curling and uncurling itself like an insect.

‘This won’t do,’ muttered Nathu, grinding his teeth. ‘It is beyond me to kill a pig. This damned pig will be my undoing.’

It occurred to him to try turning the pig over on its back by twisting its hind leg. He slowly moved towards the middle of the room, his left hand aloft, holding a dagger. The pig, which was walking along the left-hand wall, on seeing Nathu, stopped in its tracks and instead of breaking into a trot, turned and started walking towards Nathu. It grunted menacingly. Nathu slowly stepped back, his eyes on the pig’s snout. Both confronted each other. The pig advanced towards Nathu, making it impossible for the latter to catch hold of its hind legs. The pig’s eyes looked red with rage. Who could tell what the pig was up to? Nathu was losing his nerve. It was already past two in the morning. There was little chance that the job over which he had been straining so hard since last evening would be done before daybreak. The sweeper would be there with his push-cart, and Murad Ali would turn from a friend into a bitter enemy. Anything could be expected of him if the job was not done. It could mean the end of getting hides to clean; the fellow could have him evicted from the premises he was occupying, get him thrashed by a goonda and harass him no end. Nathu felt extremely nervous. He feared that even if he succeeded in catching the hind legs of the pig, the pig might kick him and free itself.

Suddenly a wave of anger rose within him and he felt furious. ‘It is now or never for me,’ he muttered and turning around picked up a slab of stone lying on the floor below the alcove. Holding it high over his head, he came and stood in the middle of the room. The pig was sniffing at the rind of a watermelon close to its forelegs, its bloodshot eyes blinking and its little tail swishing. ‘If it does not move,’ thought Nathu, ‘and the slab falls pat on it, it may break a bone or two or maybe one of its legs. That too will be something. At least the damned creature will not be able to walk.’

Balancing the slab in his hands Nathu threw it down with all his might. The flame in the clay lamp trembled and shadows flitted across the walls. The slab fell on the pig with a loud thud. Nathu stepped back and looked hard at the pig. It was still blinking its small eyes and its snout still rested on its forelegs. Nathu could not say whether the slab had caused any injury.

The pig grunted and began to move, its bulky frame swaying. Nathu stepped aside and crept close to the door opening into the courtyard. In the quivering light of the clay lamp, the pig appeared to be moving like a dark shadow. The slab had hit it on the forehead, due to which, it seemed to Nathu, its vision had been affected. The pig was heading towards Nathu, and fearing that he might be attacked, Nathu opened the door and rushed out of the hut.

‘What a nasty trap I am caught in,’ moaned Nathu as he came and stood by the low wall of the courtyard.

The cool fresh air brought him some relief. It caressed his sweating body and rejuvenated him. ‘To hell with all this! I care a damn whether the vet gets the pig or not. I am through with the whole business. Tomorrow I shall hand back the five-rupee note to Murad Ali and with folded hands tell him that I couldn’t do the job, that it was too much for me. The fellow will be cross for a few days but I shall manage to bring him round.’

He stood by the low wall and waited. The moon had risen and the entire area around bore a mysterious and unfamiliar look. The mud-track in front of the hut which, during the day, resounded with the creaking of bullock-carts and the jingle of bells round the bullocks’ necks was now silent and deserted. Deep fissures had been cut into the road by the rolling wheels which had ground the soil into powdery dust so deep that if an unwary person walked into it he would find himself knee-deep in fine dust. On the other side of the road was a sharp slope that descended to the flat ground. It was strewn with dust-laden thorny bushes which, under the light of the moon, looked washed and clean. At some distance was the cremation ground with two mud huts, one of which was occupied by the caretaker. There was no light burning in them. The caretaker had got drunk the previous evening and had babbled away till late in the night, but now all was silent. Nathu suddenly thought of his wife, who would be sleeping peacefully at this moment in the colony of the chamars. Had he not got into this mess, he too would have been in bed beside her, her buxom body in his arms. Suddenly he felt an intense longing to hold her in his arms. She must have waited for him, God knows for how long. He had come away without telling her anything. And now he missed her terribly, even though he had been away from her for hardly a few hours.

The dusty track, after some distance, turned towards the right and sloped downward. A little removed from the track stood a country well, which too, with its wheel and string of pots looked quite picturesque in the light of the moon. At some distance, the track joined the metalled road going towards the city, turning its back, as it were, on the lonely, flat, deserted area.

Far away, towards the left, stood the piggery, while all around was a vast, barren tract of land, with thorny bushes and stunted trees growing here and there. Far into the distance, hours of wa

lking distance away, stood rows of military barracks, one long row behind the other.

Nathu felt weak and limp. How he would have loved to rest his head against the low wall and gone to sleep. Coming out of the hut had been like stepping into a different world, bathed in moonlight, with a cool breeze blowing. He felt like crying over his nightmarish situation. The dagger in his hand looked odd and irrelevant. He felt like running away from it all. The next day the purbia would come looking for the pig and, on seeing the scattered hay, would locate the pig inside the hut and drive it back to the piggery.

Nathu thought of his wife again. His troubled mind would find comfort only when he lay by her side and conversed with her in soft, confiding tones. He longed for the torture to end and to go back to the haven of his tenement in the chamars’ colony.

The tower-clock struck three causing Nathu to tremble from head to foot. His eyes turned to the dagger in his hand. The thought of his predicament and the fate that awaited him was like a stab of pain. What was he doing here when the pig was still alive? The sweeper would be here any minute. What would he tell him? A faint, yellowish tint had already streaked the inky darkness of the sky. Dawn was breaking and his task was far from over.

In desperation he turned towards the hut. He opened the door softly and peeped in. In the dim light of the clay lamp, the pig lay motionless in the middle of the room. It looked tired and exhausted. ‘It should not be difficult now to kill the beast,’ thought Nathu. He shut the door behind him and came and stood under the alcove, his eyes on the pig.

The pig lifted its snout which had turned red. Its eyes appeared to have shrunk. Behind it, at some distance, lay the stone slab which had been thrown upon it. The flame in the clay lamp flickered again and in its unsteady light Nathu thought the pig had stirred. He stared hard at it. The pig had actually moved. It walked ponderously towards Nathu. It had hardly taken a couple of steps when it staggered and emitted a strange sound. Nathu, with his dagger raised high, sat down on the floor. The pig took another couple of steps when its snout drooped to its feet, and before it could move further, it suddenly fell down on its side. There was a violent tremor in its legs and they soon stiffened in midair. The pig was dead.

Tamas

Tamas